I was totally gobsmacked when I came across Lisa Hill's review of my debut novel, The Last Asbestos Town. It's amazing what you find!

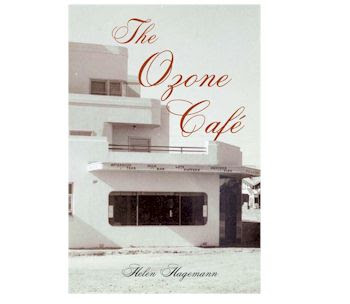

Although my novel (1st Edition) was published in 2020, I have only recently found Lisa Hill’s review on her website ANZ LitLovers. Written on 18th February, 2024, it is a fortuitous find for any author. At the time she also kindly reviewed The Ozone Cafe and said she purchased the Asbestos e-book. Thank you, Lisa!From Lisa Hill @ ANZ Litlovers

Right on cue, I was part-way through reading a novel about asbestos removal when an asbestos panic erupted in New South Wales. Helen Hagemann’s novel is set in WA, but it’s in Sydney that playgrounds, parks and schools in Sydney have been closed, a Mardi Gras party has been cancelled, and hundreds of sites have to be inspected. The culprit appears to be contaminated mulch, which is used widely in all sorts of places, causing widespread alarm because there is no safe level of exposure to asbestos.

Synchronicity, eh?

This is the blurb from Hagemann’s debut novel, The Last Asbestos Town which I bought after I had read and enjoyed The Ozone Cafe, (2021, see my review).

An Australian National law has been passed and a group known as the Asbestos Task Force (A.T.F.) is formed by the government to systematically remove all known asbestos from towns, cities and suburbs. The city of Perth, Western Australia and surrounds have undergone this removal, and gradually the task force spreads further afield into the South West. Their target has reached Farmbridge, an old pioneer town with numerous asbestos houses and buildings. Newly married, May and Isaac who plan to renovate their home, an old Girl Guide Hall, experience the imminent threat of losing their home after receiving their fateful letter. Believing their home is not made from asbestos, the couple set out on a relentless quest to save the hall from demolition.

Upfront, I’ll say that I would not have continued reading this novel if it had been promoting some sort of conspiracy theory nonsense that denied the dangers of asbestos. But no, The Last Asbestos Town is more about the kind of bureaucratic heavy-handedness over which governments sometimes preside. Sometimes this happens because it’s cheaper and easier to deliver a one-size-fits-all solution and there’s not enough staff to fix the problems that don’t fit into the program, and sometimes it’s because in the haste to do something and be seen to be doing it, a program is put into place without the proper checks and balances . Whatever, sometimes it’s just too bad for some unlucky people who are either drafted into somewhere they don’t belong, or, conversely, who are excluded from something that they really need. Whatever side of politics we’re on, we can all think of examples that exemplify an unresponsive bureaucracy that’s not getting it right for everyone.

(And, to be fair, we can also think of government programs that are very good indeed, and that help the people they’re supposed to help. Truth be told, that happens because there’s an effective, competent bureaucracy.)

Set in a recognisable future in a town that features a street with a notorious name in the history of asbestos in Australia, The Last Asbestos Town features a young couple who are convinced that the property they’ve bought is built with a product that looks asbestos, but isn’t. The thing is, asbestos can’t be identified just by looking at it. A sample has to be analysed.

And in the meantime, the task force is on its way and might well slap a demolition order on the property before their sample comes back from the laboratory.

Read the rest of the review HERE – Book Cover is 1st Edition