Tilting theTrain

Looking at my watch I notice that I have just missed the

5.10 train. Of all days, I am wet through standing on the Summerville platform,

the wind howling along the tracks all the way to the coast. I am alone, except for an old drunk swearing

into his tattered mac; most probably, his anger rising from an empty swig of a papered

bottle.

5.25pm and my

pacing begins. Except now the station is filling with people for the Stirling

line. The drunk has disappeared replaced by tired white-collar workers. I walk

along the edge, close to the tracks, my head down as I pass the newly arrived

commuters. Most have fingers on the pulse of their mobile phones or there’s one

guy, a good looking Colin Firth- type, talking to his beloved; throwing his

head back now and again, laughing as if he is happy. I imagine him going home

to a talk blonde, a woman of impeccable stature and means, re-heating a lamb

curry in the microwave. Lucky her! Since Marcus left, my meals are made by

Weight Watchers. I usually throw the packet in the microwave, sometimes adding

some grated cheese or added peas and broccoli. That ABC Checkout is right, they

do look like shrivelled images when they come out. Usually I’m too tired to

cook after a long day at Martin Sawyers. Oh yes, the notorious criminal lawyer

who represents the bad John Does of this world, when they’re in trouble. One of

the John Does gives me a wink when he comes into the office. How can that be bad?

I don’t mind the attention, the eye-candy.

Finally the 5.30pm arrives,

offloading people for the inner-city car parks or for those heading to the

Oxford Street bars and cafes. My quiet

contemplation is interrupted. A woman standing beside me yells and points

towards the middle carriage of the train. A man runs to the driver yelling.

Tens of people are milling beside the middle carriage and I can hear the

shouting above my earphones.

I take a few

photographs of what is happening. A young man who was ready to leave the train has

caught his foot in the gap between the train and platform. He’s just sitting

there. There’s panic in the air, and people yelling, ‘Don’t let the train

leave!’

In seconds, the

train driver arrives with an assistant. They try to lift the man up from

underneath his armpits, but they can’t budge him. The train crew methodically

call to several passengers to assist, waving them over and pointing towards the

windows of the carriage. A rather tall man is standing next to me, conducting

the scene. ‘I’ve seen this sort of thing

before in Singapore,’ he says. ‘Best way is to use soap. Get some soap!’ he

shouts.

‘I want to know

what’s going on. What is he saying?’ I raise my head above the melee of people

gathered near the carriage, but see little.

‘He’s asking them stand

alongside, to push their weight away from the man, but I can’t see that

working.’

‘What are they

doing now?’

‘The driver’s

asking everyone to get off.’

I move away and take more photos. Just as

well, the know-all’s constant yelling is beyond favour and subsequently I find

a space further along the platform and use my iphone on zoom. This is such an

incredible moment. It’s as if there is one combined understanding to free this

man. No one is arguing, and with quick decisive action about fifty people including

bystanders and rail staff physically rock the train. One of the staff lowers

his arm to the count of three, 'One, two, three, push,’ he orders.

The train tilts and moves from its suspension;

the force holding it for a few seconds.

The man frees his

leg.

We all clamber back

onto the train.

We pull away from

the platform.

The tall fellow has

further things to say to me as I find one remaining seat.

‘I thought it was always

a bit of a joke “to mind the gap”, but I think all of us will from now on,’ he

laughs, leaning into his own reverie.

The

hammer lay on the ground like a heavy paperweight. The feebly constructed gate

kept falling over in the wind. Alice knew that two small vegie crates wouldn’t

keep the dog in, but she continued with her project, adding cardboard and a

pallet given to her by a neighbour. That too, fell over, letting Buster out to

bark at the wind, the neighbours, visitors, tradesmen, couriers. After a week

of chaos in the new triplex, Max said he’d had enough. ‘We’re going to get rid

of the dog.’

‘No we’re not. He’s just doing his job.’

Alice viewed Buster’s antics as

humorous, running from backyard to front door, climbing on furniture, gnashing

his teeth at window glass. He’d never had so many visitors. But Max couldn’t

deal with the incessant barking. ‘We’re going to do the deed, today. I don’t

want any arguments, Alice. What if he bites a tenant? This is a business

remember. It puts food in our mouths.’

‘You take him to the bush, yourself.’

‘You have to come with me, hold the dog

on your lap. I can’t drive and hold him at the same time, can I?’

‘What do we tell the children?’

‘What do they care? They only ring when they

want money.’

♀

After

leaving the main road, the car bounced along a furrowed trail. Max had the

stereo up loud, playing Back to Black

by Amy Winehouse. It annoyed Alice, him thumping the steering wheel to the

song.

‘Can you turn that off?’ she said. ‘I’m already feeling depressed about today.’

Inside the pine plantation, he turned the

engine off, slowly easing the car between two trees. The area was filled with

neglect; potholes dipped in patches, and on higher ground loose limestone

stretched powder-like along a dense tree-line where larger rocks bordered

hummocks of pine needles.

Alice

entered the pines like a child would, prodding her feet slowly across the

ground as if some animal trap or sucking quagmire lurked beneath. She unclipped

the dog’s lead, letting him run further in. The car boot creaked, and Max

rattled metal before slamming it shut.

She watched Buster sniff in the rye

grass, cock his leg on the base of several stumps. His scrawny body darted left

and right, his coat like the bush around him, grey like coalsmoke. Along

Wanneroo Road, then into Pinjar, the colour of passing farms had yielded a dry

mustard colour like wheat-fields. Now in the undergrowth of tall trees, the day

turned dark slate. The whole pine forest seemed to take on the same hue. When a

tree spat its needles onto her shoulder, Alice stumbled down a soft incline.

With the help of an exposed piece of metal, she pulled herself up. Clinging to

its crossbar, she eased her body around it. Taking two more steps, she

discovered buried car bodies mounded like a cairn of tree and leaf litter. There

were two cars, the chassis and axle of one, and the other an upended Falcon

station-wagon, exposing its rusted wheel rims.

A small eucalypt had managed to flower in between the wrecks, a wild

horticultural image amongst tortured metal.

Alice stood for a moment brushing her

skirt, watching her husband in disbelief. Max snorted and spat as he carried

the 0.22 rifle over his shoulder, his old Akubra drawn down over his eyebrows,

making him look like some bounty hunter. She felt trapped in a bloodthirsty

movie. How had they come to this? Why was she meekly going along with his plan?

What if he missed when he fired the gun? Thinking now, she wished she’d taken

that piece of crate wood — that makeshift fence with a hundred rigid nails —

and whacked Max across the back of the neck. Alice’s mind was back in her yard,

belting him into the ground, burying him beside the petunias while the animal,

tongue lolling with contentment, sat beside her as she sipped a tall iced

lemonade.

But then the day cut its way back in. ‘A

simple gate, Max. That’s all.’

‘No I said. What is the point spending

all that money on a brick wall and jarrah gate, when I’d have to pull the whole

thing down? How many times do I have to repeat myself, Alice? The dog is a bloody

nuisance.’

Alice mulled over the last few days, Max

pacing the driveway, the ranger giving him a $100 fine, tapping out a warning

with his biro. Buster had bitten a neighbour’s child as she bent down to pat

him. Later, her face swelling to a bruised third cheek. The little girl glared

at Alice on occasions when she left for school. She wished they’d never bought

a Silky Terrier. A docile Labrador would have been much better. But when it

came to it, he was just territorial, a pint-sized guard dog, not much bigger

than your ankle.

Alice recalled the day when they first

collected Buster, going to a workmate’s house, the litter of puppies running

around, stumbling in and out of their basket; the feisty one licking her hand.

She should have got the last of the females, but the little ball of energy made

her laugh. And he’d jumped on her lap.

Now it was his last day on earth. Hell,

she thought, I can’t do this.

Max said something, but she ignored it.

Then he nudged her, rolling two bullets into the palm of her hand. He was

already loading. How these things could part and bleed flesh. They looked so

innocent. A little gunpowder, a copper casing, a life ending as quickly as

saying, auf Wiedersehen. Perhaps that

was it, that Teutonic streak in him. It came out now and again like some Aryan

dogma he had to follow. Although he denied it, he was like the rest of the

Klauss family men, hard and unrepentant, especially when it came to handling

women. Max had never treated the dog like a cuddly family pet, and now Buster’s

time was up. That was that, die Musik

fertig ist, Max had been telling her that all morning.

They walked silently into a glade and a

large field opened up that held the remains of a Massey-Ferguson. It sat

clogged with branches, collapsed like an old workhorse. The seat on the tractor

sprouted tufts of horsehair between cracked leather and stitching.

They crossed another limestone track.

‘Too

exposed,’ he said. ‘I want to go further in, over there.’ He pointed towards

the old growth trees, past hedges of new plantings.

The day darkened with the threat of rain

clouds. Lightning hissed and split the sky somewhere over the Wanneroo Raceway.

It quaked once and then again soundlessly. Alice drank from her water bottle.

The liquid seemed to stick somewhere in the stream of her throat. Suddenly it

came back up and she was choking and spitting water onto the ground.

‘I feel sick,’ she said.

‘It won’t be long now. See those thick

woods over there. That’s where we’ll do it.’

They both stopped, Max holding back the top

of her shoulders with his hand. The drone of a two-stroke engine rose and fell

away, topping a hill, then disappeared into a gully.

‘Damn trail bike,’ he said.

Max scuffed and stomped his black boots

into the pine needles, an angry line of sweat dampening his sideburns. Alice

wondered if that nervous tic in his neck was some indication of more trouble.

He was flicking out a hanky from his pocket, wiping the band’s indentation on

his forehead, replacing his hat and scowling. ‘A person can’t even take a

stroll in a bloody pine forest without some hoon trailblazing. On a Tuesday,

for god-sake!’

Max stared at Alice while she dropped her

eyes. ‘Bastard! We’ll have to wait until he’s gone.’

‘Hide the gun,’ said Alice.

‘Why? We could be shooting rabbits.’

‘I hate this. Let’s come back another

day, please Max!’

And to herself she was thinking she’d

ring the Animal Haven, have the dog picked up straight away. Perhaps, Bill the

dog-sitter, they used on holidays once, would know what to do.

‘Where’s the dog gone?’ he asked.

‘He was here a minute ago.’

‘I told you to keep him on the leash,

Alice. You can be stupid sometimes.’

‘This is not exactly my idea of fun. I’m

going back to the car.’

‘Oh, so now I have to fucking-well find

him.’

‘That’s your problem.’

Alice turned from the deep ruts of pine

needles, the carpeted vehicle wrecks, and walked back along the dirt road. She

felt slightly disoriented. Where was the car? Then an inbuilt sense gave her

the number three. Yes, they’d crossed three tracks. The car was sitting back

there on the third road.

She hurried through the pines, and

reaching the second limestone track past the open field, looked back. Max was

nowhere in sight. The forest sulked to a dark grey, and an evening mist wheeled

its way in. She shivered, feeling the cold air on her arms, slapping herself

warm. She wanted to run, but couldn’t. The forest floor was dense, opening up

like a part of hair where she trod. She was in the darkest part of the

plantation, and the haze continued to wrap itself around the trees like a long

grey scarf. She thought she heard a voice, a kind of rustling. She could see a

misshapen figure further up.

‘Hello?’ she called.

She swept an arm into the air, and could

only hear an eerie fluttering. The haze thickened and the distant trees stood

like cold alpine sentries. Alice’s legs ached from standing too long. She

shifted from side to side, and wondered why this person was taunting her.

Defiant, she yelled out. ‘We’re killing a dog in here, today. What do you think

of that? Be careful, he’s got a gun. He might kill you. He threatened to kill

me once, if I ever left him.’

She

stood watching, her voice winding down to a pathetic moan. ‘Well go on,

disappear then, don’t try to help.’ Then she called out again. ‘He’s got four

guns, a double-barrel shotgun, a BB gun, a Smith and Wesson revolver, and a

0.22. It’s a marriage of guns and bullets. Living with a bully! And what do you

think I am? A quiet hick-town mouse, huh? Never amounting to anything, huh?’

Alice lifted the fur of her collar, and puffed on her fingers. ‘No, I’m going

to university,’ she said, slowly. ‘Hey,

you, over there!’

Alice grew tired of waiting. And then a

bounding sound and a crackle of leaves amongst the pine litter made her stretch

her eyelids as if focusing into binoculars. First she saw a large kangaroo,

then another with a joey trailing behind.

‘Bloody hell, I’m talking to a bunch of

kangaroos.’

She moved away, muttering that they

wouldn’t be interested anyway. ‘Would you?’ she said to herself. Along the

second track, an iron bed frame came into view, its springs skewed and rusted.

Carloads of rubbish lined the side of the track, old televisions, lounges,

cardboard boxes, auto-parts, and a spread of mildewed carpet and cracked

ceramic tiles. She crossed over onto the final road and could see the car

ahead, stark white against the dusty green trees. A loud phalanx of Carnaby

cockatoos flew overhead and a strip of sun brightened the ground, warming her

back as she walked. She didn’t notice them before, but the car was surrounded

with patches of apricot spider-orchids. She gathered a handful, and

unintentionally pulled out bulbs, and began shaking the peaty soil from the

stalks.

A

loud crack rang through the forest. Its short burst detonating the air like the

first whack of a whip, cutting the day in two. First a sharp menacing sound,

then a hollow silence followed. Alice leant against the car boot, and slowly

slid to the ground, her auburn hair catching on the bumper-bar as she went. She

gathered in her pleated skirt, wrapped her arms around her knees, buckling her

stomach in. With the finality of the bullet, everything tightened, hands, neck,

calves and toes. She shut down, then rocked and heaved and moaned.

‘What are you doing?’ Max said, coming

towards her from the front of the car.

Alice, startled by his sudden presence,

squirmed, and raising herself up slowly against the car, she let the flowers

fall from her hand.

‘Don’t ever ask me to get another dog,’

he said. “That was the worst thing I’ve

ever had to do.’ He hurled the rifle onto the back seat, and slapped in the car

door.

♀

The

car bumped its way out of the pine plantation. Alice looked out of the window

at the black clouds forming overhead. For a long time, she clutched her hands

over her stomach, then started to smooth the creases in her tights, rubbing a

peat stain with a wet tissue. Crows pecked at a roadside kill. The sky had

turned from a dark slate to coal. She looked at her husband, the composed side

of his face, his rigid, faraway stare, and went back to black.

The Colour of Hush

All the stores disappeared. Alice didn’t feel like working

the sewing machine. What was the use of doing all the hemming when her mother could

no longer sell her dresses. She wanted to play instead of work. She liked

collecting odd specimens of rope, fishing line, or a plastic bucket left over

by holidaymakers. Once she found a pair of thongs that flapped loudly on the

concrete. Spread out in the sparse Buffalo grass, Alice made little pathways

with pebbles, twigs and leaves like a miniature Brownie campsite. At Christmas,

she rain-bowed every page of a Disney colour-in book. With her new sixty-four

paint-set, she detailed and glazed Plaster of Paris moulds. Standing back and

casting her blue eyes over Donald, Minnie, Goofy, Daisy and Mickey she

pretended they were part of the St. George football team.

♀

Earlier in the day, Alice had asked to climb the tree house

that Jimmy and his mate Fizz had built in the laneway. The cubby had a door, a

tin roof and a platform made from dad’s hardwood planks from the back of the

shed. They had even nailed ladder-boards up the trunk. But the Smart Alecs were

on the deck, yelling, ‘Bugger off, Alice!

No girls allowed!’

‘Up yours then! I’ve got something better to do.’

With the sun sending intermittent silver rays through the

backyard trees, Alice heads for the coolness of the shade and a stack of

bottles piled along the Chin’s fence-line. She rolls some with her foot,

letting the stench of fermented hops leak away. Others dangle wet and sticky

labels. She picks out several pint bottles, bearing up the milk sludge to

eye-level, wiping the dirt with her hands, clanging the cleaner ones down the

path to the back veranda and tank-stand. She can hear the far-off drone of

motorboats and likes the way the glass mirrors her big nose and cheeks, the

flapping clothesline in the background. She glances at Kevin in his sandpit,

making two lane highways with his tip-truck.

Alice’s mother, juggling her golf clubs and buggy into the

Beetle, yells from underneath the boot. ‘Alice! Don’t forget to pay the baker.

I’ve left the money in the basket.’

She nods, and in the midday heat decides to move her bottles

to the cooler westerly face of the tank. She floods the ground with the open

tap, sluicing out the sandy dregs before topping up the water.

Holding her stomach tight, shaking, wiping and stacking

bottles, Alice nearly forgets to breathe. Mesmerized by the swatches of colour,

the changing shades underneath her paintbrush, she doesn’t hear the two boys

coughing and backslapping each other behind the outhouse, nor does she catch a

faint whiff of their rolled tobacco. She is standing on a crate, lifting the

brush, dripping a mass of yellow, red or green goop into the bottles, swirling

the water, then standing back admiring her work. There are moments when the

bottles resemble Manning’s soft drink stand, Lemon, Lime, Raspberry and Cola.

Alice doesn’t notice the shadows moving across the tall rye

grass, her mother unloading the golf buggy, hosing the car, Kevin and the dog

running under the spray. She conducts an orchestra on glass, discovering

different sounds in the varying heights of water. If she taps the rims, a high

note. On the grooves, a low thud. She listens to the pinging sounds of the

tank’s corrugations cracking in the sun, and hits the tank-stand’s wooden ledge

continuing up the rungs of metal. The melody heightens along with a familiar

voice at the fence. ‘They want us at the flat for a minute,’ calls Heather.

Alice squints into the afternoon glare. ‘Which drink do you

want to buy, Heather? I’ve got Orange, Lemon or Strawberry Cola.’

‘Alice, the boys want us to play at my place. If we come,

they’ll let us climb their tree-house.’

‘But I don’t want to. I’m playing with my bottles.’

‘Just leave them. They’ll be here when you get back.’

‘Do we get to join their club?’

‘Soon as we’ve done what they want.’

The girls walk through the Chin’s front yard and head

towards Broken Bay Road, Alice wiping her paint stained fingers on her red

jeans. ‘What do they want this time?’

‘I don’t know, but we’ll be the only girls allowed in the

cubby. They don’t want Judith because she’s a bossy-boots.’

When they turn the corner, the boys are skylarking on

Heather’s lawn. The house on the high side of the street has a large portico,

trailing geraniums, and the name Emmanuel above the door. The dark house was a

portal to games of Ali Baba, surprises in large wardrobes, hide and seek. After

school, they switched the piano over to the Pianola, rolling scrolls of

honky-tonk, Winifred Atwell ghosting the ivory keys. Mostly they dragged out

the dolls, Snakes and Ladders, or Chinese Checkers. Alice liked the way her

sandshoes rippled like sticky gum over the kitchen’s soft cherry lino. The

larder was full of cream biscuits, Saos, cheese and Vegemite, and the backyard

had a swing amongst orange, mandarin and loquat trees. Mr. Rundel had two

vintage cars. The girls often sat in the dark green M.G. pretending to be Mole

and Badger from Wind in the Willows. The Rundel’s were hardly ever home. René

was either at the doctor’s or choral practice, and Heather’s father worked

double shifts at the Mt. Penang Boys’ Home.

Alice thinks about the bottles sitting on the tank-stand and

hopes they won’t discolour or smell. For a moment she imagines old Miles’

ginger cat smashing them on the concrete, or holiday arrivals tossing them out.

On an upper level to the road, the boys are karate chopping

the spaces between the Rundel’s pickets. When the girls open the gate, they

roll around each other like balls in a pinwheel. Jimmy struggles for air, while

Fizz hooks him in a strangle hold, bending and moving knees towards the garden.

Alice finds she‘s been tricked. ‘You boys are stupid.’

Looking at her, they collapse into a box hedge, four feet

and arms lying belly up. Until they spring up from one another, hands held out

flipper-like. They’re pumped and sweaty, prodding, corking knees and thighs.

Fizz whirls Jimmy around, hugging him into his stomach. Facing the same

direction, Fizz’s right foot locks into Jimmy’s soft thigh, heaving him onto the

ground. With begging hands in the air, Jimmy stands in front of the girls, his

flushed face matching the irritation in Alice’s eyes.

When they enter the back rooms of an outside flat, Heather

cups her hand and giggles into Alice’s ear. ‘They want a root,’ she says,

flashing her eyes boldly towards Jimmy.

‘You know what rooting is, don’t you?’

‘Yep,’ says Alice, looking puzzled over Heather’s shoulder

at Fizz, his head bent to the floor. She gazes at him, moving her eyes

rhythmically over his body, until they catch a quick glance from his.

‘Jimmy and I are going to do it in my bedroom. You and Fizz

can go in there,’ says Heather, holding back doorway beads on an old iron bed

in the corner.

Alice was alone with a boy she grew up with. They went to

Sunday school together. She felt herself drawn along by Fizz’s sticky hands.

She had a delicate sense that he must have liked her, so she let his tickling

fingers find their way inside the elastic of her undies. She lay silent the

whole time, stretching her bare legs like anchors into the shell-like pattern

of the bed quilt. He tugged at his shorts and then she felt his stomach warm on

hers. She liked the way their skin touched, his hand turning her head to kiss

her beneath the eyes, but suddenly she shifted higher on the pillow and his

forehead bumped the bridge of her nose. He held her face while his thin lips

smacked into her mouth. It lasted so long Alice couldn’t breathe. Then he was

telling her, ‘I’m glad you’re not wearing lipstick yet. I hate lipstick.’

Fizz no longer had a childish voice, he was moaning and

groaning like one of Tarzan’s jungle animals. He was hard against her, bumping

wildly in the air as if the veins in his arms were about to burst. He was wild

and out of control. Alice just lay there thinking about the dogs she had seen

in the street. The male did all the work. She wondered if the soldier crabs

that carried one another on their backs were rooting as well. Fizz was poking

her with his fingers, turning the little mound of flesh in and out, picking a

point between her legs where he could wade deeper with his dick. She heard

Heather’s girlish giggle on the back steps, heard the drag of matches. They had

done it, she thought, and now Jimmy was letting Heather smoke his cigarettes.

He thinks he’s so smart, like a cool Humphrey Bogart.

Fizz kept on and on, mooning over her, swooning and swaying,

looking northward into the window, then back again, pushing his tongue into her

mouth. His bottom rocked and his thighs circled and probed. Alice let the

sensation wash over her as if the tossed bed was a tangle of seaweed. There she

was gripped like a trawled fish. When he gave out little grunts and puffs of

air, she thought of him caught in a rip, legs cramping in a full roll of surf.

Then reaching the shallows, he raised his stringy body up and moaned as if

coming out of the waves, exhilarated that he hadn’t drowned.

When he rolled off her, Alice thought that Fizz must love

her. She couldn’t remember the last time anyone had ever kissed her so

tenderly. He was good at French kissing, he said. Sunday school drifted into

her thoughts again, the mental picture of Mr. Pendlebury in the pulpit, his

whispering voice hissing on and on about sin and damnation. She thought about

Betty Parker’s wall print showing heaven and hell, Christ walking with the

lions, and now here she was on another path, heading towards the gambling

houses, where the corseted ladies sat at bars, where the fiery furnace enticed

sinners. He must love me, she thought. Maybe he’s just being nice because I

don’t have any tits. She found herself rambling. ‘I can’t find my pants, have

you seen them? My other sandal is somewhere. When is your mother coming home?

Don’t worry about the cubby. It’s dumb!’ But her questions were met with a

piqued silence, as if her raw flesh, the kissing and fondling of her fanny had

suddenly become the lost part of a Chinese whisper.

She scowled at Fizz. Had he forgotten she was there? He was

shrugging his shoulders in front of the bureau mirror, flicking out a comb from

his top pocket, peaking black hair into a Tony Curtis ducktail. All the smiles

and niceties had disappeared. ‘So, it’s a big joke?’

Alice ran out the door, past Jimmy and Heather on the steps.

She flung herself through the back gate, slamming it shut with her shoulder.

Tiptoeing past Mr. Gettoes spraying his tomato plants, she skirted Mannings’

double garage, halting for a moment to slam the tree-house rope hard against

the laddered steps. She moved quickly through the Chin’s wire fence, and

crouched near the Zamias listening for any noise of holiday arrivals. Satisfied

the house was empty, she settled herself inside the double toilet, cupped her

face, digging her elbows into the tops of her legs.

She could hear the boys in the laneway, calling to her. She

could have a free tour of the cubby. But she sat there in silence, her undies

caught in a figure eight at her ankles. She heard Fizz talking to Jimmy. ‘What

if she tells?’

‘No, she won’t. I know her.’

‘She’s not home, Jimmy!’ yelled Heather from the back porch.

‘Your mum says she’s with you.’

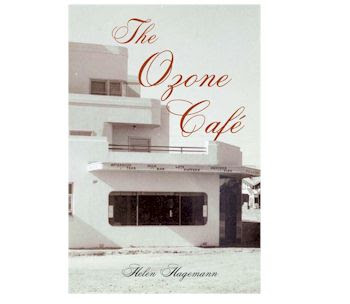

Just a few yards away at the back gate, Alice could hear the

boys discussing the Ozone Café, or was it the beach? She didn’t dare move or

pull on her panties just in case they heard the squeak of the lid, or her

sandals on sand.

‘She’s probably sulking somewhere in a boat,’ said Heather.

When the afternoon had spread its country silence, Alice

pulled up her panties, washed her hands at the little basin and emerged from

the outhouse. The sky darkened under cloud and in the two hours while she was

away the thick paint had bottomed in the glass. She noticed the split colours,

how the water had turned a milky yellow or pink on top. She wondered what would

happen if she put all the dark shades inside the bottles. Would the rich reds

or green stay at the bottom while the inky colour floated on top? She opened

the paint tin, oven-hot in the harsh sun. Some of the colours had run, the

blues and yellows melting into a variegated-green slurry. She hadn’t used the

charcoal, grey or black. They were still hard little rectangles. She scraped a

small amount of water into them, and wiping the slush from the edges with a

hanky, gouged deep holes with her paintbrush.

The grass whispered behind her. She didn’t pay attention to

the ginger cat slinking under the house, a lizard sauntering the piebald stump

or ants building tiny moon-craters in the broken concrete. The dog, tugging at

the fence and running back and forth along the chicken wire, annoyed her. ‘Go

away, Princey,’ Alice shouted. ‘Go play with your ball somewhere else, you

stupid dog!’

The nature of things no longer interested Alice. She wanted

to ruin the perfect rainbow colours, so she dripped black sludge into each

bottle. ‘It’s just stupid to think you’d stay the same. Now you’re black,

black, black!’

Bent over the stump, she made a sooty paste across the

surface of her paint-tin, turning every pristine square to the colour of night.

She didn’t hear the jingle of Heather’s bicycle, as she filled the bottles with

black sand.

‘We were looking for you,’ said Heather.

‘I don’t care about the cubby,’ she said, defiantly.

‘Look, Alice, it’s just like playing doctors and nurses.

Anyway, Fizz wants to talk to you.’

‘What for? ‘

‘Oh, come on! Come back. We all want to have a smoke.’

‘Did you do the drawback?’

‘I tried, but Jimmy’s going to show me how to blow smoke

rings. Come on, please! I don’t want to be the only girl.’

Heather stomped her shoe on the bottom rung of the wire

fence, urging Alice through the space stretched by her hands and feet. Alice

looked back at the black stains on the bleached timber slats. A kind of gravity

pulled her along. She’d liked the kissing part, but Heather just laughed about

boys’ smelly armpits, turning the conversation to dark red lipstick and her new

trainer bra. Alice could only wonder about the rubbing motion Fizz made between

her legs, his sweaty face locked in little clicks, the pearl drops squeezed out

and onto her belly.

Separation

Gary wiped his fingerprints from the front

of his i-phone. Modern communication now had meant that Clarabelle could

contact him anywhere, anytime. He wasn't sure if that was a good thing.

Although the dry spinifex country could take a man to his knees, gasping, dust

settling down on his dry bones, and he didn't want to be another statistic.

‘When

are you coming home?’

‘I’m

not sure, most likely at the end of the month.’

'Gary, I need a date. Sylvia and Larry are coming all the way from

Cloncurry and of course, they want to see you!'

'What do they want to come to Perth for? There's plenty of other places

they could visit England, New Zealand, America.'

'They want to see Ben, too.'

'Bloody hell. Do they know how important my work is?'

'Are the new seeds taking?' she said quickly, as if to change the

importance of the question with a quick breath.

'The wind and the dry conditions haven't helped.'

The Donkey Orchid, known as Duiris, is a

genus of herbaceous plant belonging

to the orchid family.

He

had been in the Kimberleys for three months, replanting the orchids, spreading

seeds and looking for an undocumented species known as duiris flexiosa. Commonly known as puce flexiosa it was indeed rare. The main problem was that this

miniature orchid with the big ears had profusely and unnaturally propagated

with the 'Happy Wanderer' brachyscome

multifida, a wild rambling ground cover that once it took over it was, you

may guess, as stubborn as a mule.

His main mission was to stop the donkey from bolting further off into

the bush. Of course, it wasn't like that exactly; he wanted to stop the plant's

migration, bringing it back to its original, non-variegated state.

The Donkey Orchid is logically derived

from the appearance of the two lateral

petals, protruding from the top of the

flower like the two ears of a donkey.

Clarabelle rang him fortnightly at first, then every week, mainly to

find out if he'd advanced further into the granite lobes and gorges. He told

her he was still camped at Parry's Lagoon, collating, keeping his journal

up-to-date. 'I'll head out soon as I've finished', he said. 'Stop calling me

every five minutes, I don't have time to chat.'

Since the cattle musterers were planning a trip to Western Australia, he decided he could take his time in the gorges. He knew it wasn't all holiday for the Pratts. Oh, no! They'd be buying cattle for Georges Downes. He'd met Larry before on their Queensland holiday. It was always a hard slap on the back from big Larry with the Stetson. They can wait, he thought. I'll get lost for awhile, no mobile, battery gone. Heaven.

The next morning he set out for Barren Mounds, along the Derby Gibb

River Road. He had heard about an exotic orchid growing in the region, but

botanists had almost given up on its whereabouts. He's seen them catalogued

once in 1989, lime green dorsal petals, white wings, mauve lips.

The hermaphoditic flowers grow solitary or

in several-flowered loose racemes.

Colours vary from a lemon yellow, yellow

and brown, yellow and purple, yellow and

orange to pink and white or purple. The

two lateral petals are rounded or elongated.

The dorsal petal forms a hood over the

column.

When

he was packing his outsource camp, he noticed that his rations were getting low

and this year the cyclones hadn’t arrived to fill up known waterholes. It was

another four hundred kilometres back to Fitzroy Crossing, so that wasn't an

option he was willing to risk, time-wise. The Rodeo was on half empty, but the

fuel gauge was as temperamental as his old grandfather's clock. It moved when

it wanted to move. He had a spare thirty litres in the jerry can. It felt

better in his head to know this. He had other things on his mind, circling

around like a blow fly on Benzedrine. When he was packing the trailer with his

small tent and his ground equipment, the barometer continually pointed to 'high

and steady'. Two weeks into the trip and in these hot plains, especially the

mountainous terrain, no matter what hour in daylight, he needed to know when

the needle changed signaling wet weather.

His water was low. He'd have to take small sips on his flask and cease

shaving. He looked in the rear-view mirror at his growing stubble. His wire-mat

of pin-prickles was already itching. He would be like dog every morning

scratching every inch in an upward direction.

He

headed further north, the corrugation of the road almost bumping him out of the

cab. This was always the way, once you left the main road, dust like cayenne

pepper getting into the engine, air-conditioning vents, the nostrils. Such flat

country he could make out the Barren Mounds in the distance. Upturned ochre pots

baking in the sun. Further ahead, the gravel was thinning out into furrows of soft

granules. He could see a mirage line trailing left to right across the road,

never reaching the vehicle, always staying ahead like a veiled dewdrop.

The Princess was calling. That's what he called the orchid, Princess

Diana. His colleagues had said, 'lime

green will never been seen.' But he had documented a similar variety of Duiris on his last trip to Mount

Augustus, a yellow green with a white coronet at its crown. He managed to

propagate several in his home laboratory. He loved touching the petals, opening

the small lips of the orchid as if parting a beautiful woman's mouth. Diana, he

knew, was somewhere in this crusty termite sand. He would find the buried

tubers, take them back to Perth and prove that the donkey orchid could

metamorphose into any prime colour.

There seemed to be a slow stratagem of time before reaching the Mounds.

Another five kilometres, he thought, but for now nature was calling and he had

to obey.

He

climbed down from the driver's seat, upending a lopsided sign. He wiped his

brow with the swipe of his hat, and took a large gulp of water. The earth was

beginning to bake. He unzipped. The trickle of his urine darkened the spot into

a little moon crater, disappearing as quickly as it came. He noticed a small

gecko running into the low scrub. The sun began to sting his back and neck.

Almost midday, the temperature had doubled since sunrise.

He

got back in the vehicle, clicked over the key. The engine chuckled at first, then

stopped. He looked at the fuel gauge. It was pointing to 'E'. 'Fuck', he said,

slamming both hands on the steering wheel. Then he had a searing thought as he

uncovered the back flap, reaching in for the jerry can. He was out of mobile

range, and with only thirty litres of fuel, he would never make it to Barren

Mounds and back. Bloody GM! Why hadn't he fixed the gauge? He did everything

else. Worked on Clarabelle's Mazda when he was home, changing the oil, spark

plugs, filters, under the bonnet changing the brake fluid. 'Four-wheel drives

are meant to be tough', she had said. It will outlast you, was her other

mantra.

'Fucking hell! It goes if it's bloody got petrol.'

He

kicked the tyres with his boots, hopping back in a rebound. When he had

finished filling the tank, he cranked up the engine, spinning his tyres into an

arc, his right foot depressed hard, his body pulsing forward and back.

He

made it to a roadhouse along the Derby Gibb River Road, close to Fitzroy Crossing.

He felt washed-out and dirty, so he decided to end the trip, go back home and

catch up with the Pratts. This was what she wanted. He would be in Clarabelle's

big smiley books once again.

* * *

He pulled into the driveway and noticed a

hire car parked outside the garage. The Pratts were already there. He needed a

shower, so rather than going into the main house, he went down the side to the

pool's outdoor shower. He scrubbed his

body of every grain of red sand, shaved and changed into some boxer shorts and a

Hawaiian shirt that Clarabelle meticulously arranged for guests. The perfume of

the body gel was a welcome change to his usual odour of sweat and stale

hormones.

He

opened the back door, placing his duffle-bag on the tiled floor in the kitchen.

He thought he would be greeted by the three of them in the lounge room,

clinking glasses of champagne. He couldn't hear any conversation or laughter.

He checked the gazebo down the back. It was often a cool space when

entertaining. Only the birds in the aviary greeted him. He went back inside the

house, opened the fridge and poured himself a beer. His head began to

free-fall, time to get into the sack. He

thought he could get some quick shut-eye before they came home, from wherever

they were, out shopping or walking along the river. He went upstairs in his

bare feet. He opened the door of the bedroom. Two bumps lay in the bed. Two

bodies clutched, moaned, a bare arse going into spasms.

'Clarabelle,' he yelled. 'What the fuck!'

And there he was, the cattle owner, suddenly turning around from his

prostrate position, his face and body reddening in the split second that Gary

had stood there, the man muttering profusely, his Stetson covering the front

view of his family jewels.

Pollination is by native, small

bees, lured to flowers mimicking flowers of the pea

family. The fruit is non-fleshy,

containing 30-500 minute seeds. These seeds mature

in a matter of weeks.

* * *Bittersweet

Wednesday afternoon, and the ice-cream van melted.

It was another fine spring

morning with a slight sea breeze, so Karla decided to walk to Sean’s apartment

instead of catching the bus. After yesterday’s madness the walk of twelve kilometres

there and back would help; her mind going round and round endlessly, without a plan.

Placing her blue Converse sneakers on slowly, she slipped each foot in, looping

the two laces together like two halves of a heart.

In the town centre, her

shoes joined a thousand other shoes and were lost. At the corner of Hosken and Marine

Terrace, when most of the traffic had disappeared, mothers being swallowed by

Target or K-Mart, she stopped, lifting her water bottle from her backpack and drinking

a third of the way down.

As if looking over her

shoulder, she could see the previous day’s mess, still feeling the sharp sting

of cold. She wished she hadn’t invited him over. He was quiet at first, but

soon his smile turned to a menacing furrow when they didn’t have Strawberry

Ripple or French yoghurt. She had offered him Banana-Mango but that had disappeared

down her chest. He pretended to kiss her as he opened her t-shirt. She wanted

to call him names, instead she laughed lightly as she flapped out the cotton

material, letting the ice-cream cone slip to the floor. That hadn’t really worried her, not as much

as the mystery of the pulled power lead.

It was nine-thirty five when

she arrived at the top of the hill, past the beer factory and the children’s

playground. To her left she could see the fishermen assembling their cray pots,

freezer trucks backing up and loading. Steam rose from the estuary. It wasn’t

morning mist, but a wet haze from the humidity of the night before. Further

out, the light shone on the water like a million dancing pearls.

She could have stayed

there, watching the morning’s activities, a soccer team on the oval, people walking

their dogs. Instead, she continued on, her sneakers making a clapping rhythm on

the concrete path.

He had taught her the

guitar, at first playing a few chords. He was constant in his attention at how

she held the instrument close to her body, moving her fingers along the

fretwork.

Each day she went to his

apartment, it was sex, then the guitar. Sex and guitar, in that order. Never

guitar and sex.

Sometimes she just wanted

to sit and chat over a cup of coffee, or play with the kitten he’d found in the

park. But no! He undressed her slowly at first in the living room, led her by

the hand to the bed, gripping her undies off with his teeth. One day he did

this very act, pouring some yoghurt from a large tub over her bare stomach. He

licked the liquid up to her face before smacking his sour lips into hers.

She didn’t like yoghurt.

All yoghurt was good for was ‘verdigris’ as Aunt Lucy put it, showing her how to

a ge some copper pots. She would never eat it after that.

Sean had funny ways like singing with his

hands over his ears. In the six weeks she had known him he said there were

things she’s find out later on. ‘Secrets,’ he said, ‘just wait and see.’ She

never found out what he did for work. Only that he played some nights at the X-Ray

Café. Now the band was looking for a drummer, so the guys hadn’t been around in

all that time.

As she walked down the hill,

she could see his upstairs window. It was strangely quiet, not one car in the

street. She thought that perhaps being a Thursday the pensioners who lived in

the same building must be out shopping or paying their bills.

She crossed to the other

side of the street and stood in the shade of a Poinciana. His blue Corolla

wasn’t down the side, either. She curled her hand gently around her water

bottle, the fingers on her left hand, prickling. She poured water on them to

relieve the sting and her sweaty palms.

She knocked on his door

three times, but there was no answer, so she walked away.

Back at the house, her

father lay sleeping on the couch. She took out the mop, some sponges and a bucket,

sloshing water on the floor of the van. A gooey splodge of Vanilla ran down the

vending machine, the choc-bits leaving a track of sticky pebbles on the

linoleum and towards the door. The Banana-Mango had painted the van’s

upholstery yellow. She continued cleaning the mess, thinking over her original plan,

then another thought bubble loomed.

The next day she went to

the supermarket, to the freezer section. She’d never bought it before and was

surprised to see so many varieties and flavours; small tubs in packs of six, some

in twos, or single. Each brand stacked neatly together on the shelves above the

mousse, whipping cream, butter and margarine. She didn’t see his favourite, but

thought the large tub with the picture of mixed berries on the front would be

just the thing.

It was late when she

arrived at his place. She could hear a loud thumping coming from his amp. Sean

was in the living room just inside the front door. She could hear him and two other

males, the highs and lows of their voices travelling around the room. She

listened with her ear up against the wall. A microphone pinged incessantly,

until it stopped. Guitars tweaked into a metallic wail of strings. Then the

deafening din of drums smashed and rolled into a quick flurry, making her jump

back in fright.

She hunched down over her

bag, pulling out a piece of paper, then a paint brush. She opened the large tub

of Wildberries, wiping the edge with a tissue. She stood up and began painting the door with

the yoghurt. It dribbled down over the surface and handle, leaving a residue of

tiny giblets of fruit; a Jackson Pollock slap-on of blueberries on mission

brown. When she finished she stood back, away from the noisy thunder inside. It

hadn’t worked as well as she thought, so she pulled the door mat away, wiping

up the trail of dirt behind. Then she poured the rest of the Wildberries slowly

along the groove and into the small gap under the door. She pushed the coir mat

back up against the creamy substance that was beginning to ooze and trickle in

all directions.

She hunched down over her

bag, pulling out a piece of paper, then a paint brush. She opened the large tub

of Wildberries, wiping the edge with a tissue. She stood up and began painting the door with

the yoghurt. It dribbled down over the surface and handle, leaving a residue of

tiny giblets of fruit; a Jackson Pollock slap-on of blueberries on mission

brown. When she finished she stood back, away from the noisy thunder inside. It

hadn’t worked as well as she thought, so she pulled the door mat away, wiping

up the trail of dirt behind. Then she poured the rest of the Wildberries slowly

along the groove and into the small gap under the door. She pushed the coir mat

back up against the creamy substance that was beginning to ooze and trickle in

all directions.

She balled the piece of

paper up into her hands, pinging it high in the air. It rolled and went out of

sight as she went down the stairs.

Soon to be published in The Serendipitous Choir - an OOTA anthology

* * *

Aunt Vagna & 9/11Soon to be published in The Serendipitous Choir - an OOTA anthology

* * *

I arrived at 7

am. The day clear in the falls and shadows of buildings; a cloudless Autumn.

The Autumn they executed James Elledge Holte, and I didn’t know what I was

doing in New York.

It was a culture shock at first, standing on the corner of Fourth and Lafayette, the busy traffic rumbling by, taxis hooting

from the kerb, a truck driver yelling abuse to an open hood, steam hissing from

an old Pontiac.

I could hardly see the open sky, buildings so tall they shaded every arterial

road of the city. What day was it? I could only guess without my glasses that

history was happening on the front page of the New York Times. Large black

lettering spelling out “WITNESS TO AN EXECUTION”. I felt sick at the thought of

the words ‘lethal injection’, and Aunt Vagna’s name. Was she related to this

Holte? I would soon find out.

She lived in an apartment on Madison Avenue

and I had three hours to kill before I could see her. What did Aunt want from

me? Why the sudden trip to New York and on top

of everything paying my fare from London to Hong Kong? Finding the funds myself for the rest of the

journey. She was ostensibly the richest woman in the family. They said, she

draped fur and diamonds, had shares in General Motors and AT&T. But she

never contacted any of the family. Father said, she was afraid that everyone

would sponge, come after her wealth when they didn’t deserve it. So they left

her alone.

I remained suspicious, but curious.

I sat in an alfresco coffee shop in one of

the quieter streets, about two blocks away from her apartment. A sliver of sun

shone down between the skyscrapers and I was able to pick up the paper and read

the front page without my glasses. I must have left them in the subway when I

was juggling my backpack, discarding the paper bags, making my luggage compact.

After all, I was on foot, the pack heavy with books, the jewel box and

photographs. I knew, looking at the congested streets, that I could pace myself

around the city much quicker than hailing a cab. I could carry my briefcase and

leave my luggage in a locker, come back for it in the evening.

Free of the weight, I stretched my legs

under the table. The waiter, speaking to me in a German brogue, brought the

last cup of coffee I could manage. I asked him about the Trade Centre and he

drew a map on my serviette. I tore the map’s corner, placing it in my wallet.

I knew Vagna had one of her flower shops

near the Twin Towers. Perhaps, that’s where she was.

She couldn’t be in the Manhattan store, or Greenwich Village; that would take her past lunchtime to

meet me. Really, I didn’t know where she was.

It wouldn’t hurt to visit the shop. I opened

my journal and looked for the address. Pushing my way through the crowds, I

felt a tug on my coat lapel. I clasped my hands tighter on the briefcase.

Feeling that sensation against my jacket was odd, yet slight enough not to

suspect anything. Then I tapped my pocket. The horror of its emptiness made my

stomach rise, only to have my lungs knock hard against each other. Or so it

felt. Bastards! The two had pinched my wallet, the one in front pleading a

synthetic ‘sorry’, the other quickly lost in the distorted view of heads.

I decided to forget about Aunt Vagna’s

flower shop. I needed that wallet, especially the map, so I back-tracked along

the pavement, lifting my head intermittently above the crowd to see if I could

catch the swift footwork of the two pickpockets.

At a newsstand, I asked the guy behind a

stack of magazines if he’d seen two young men in baseball caps and moccasins.

He just answered, ‘Seen one, seen em all, Pal.’

I was devastated. Map lost. No money. No

credit cards. I’d have to report it. I tried the alleys, hoping the same two

might be waiting for me again, especially for the briefcase. They didn’t know I

had something valuable that I could bargain with.

In a cardboard-stacked alley, a Chinese cook

emptied a pail of fish heads into a dumpster. The stench moved me on. I crossed

over the main street to the other side, taking my weary legs down several

sidestreets.

I thought a storm had sprung up, the sky

darkened suddenly, people were running everywhere pointing, shouting, covering

their mouths with newspapers. Some were running backwards, elbows bent across

their faces. I poked my head out from the cool shadows into what I thought was

a dust storm. The empty space between buildings was swamped in plumed lips like

an atomic bomb. There was a loud crack and a roar in the air I’d never heard

before. This time I could see the smoke lathered grey and pink filling

Broadway. I watched shoes landing on the pavement, reams of paper haunting the

grey-cloud drizzle. I knew I had my mouth wide open. I felt charcoal on my

tongue, the full taste of it seeking my lungs. It clotted my hair with ash

fallout. I was inside a nightmare on Canal

Street, a strange movie reeling itself away before

my eyes. This was not Godzilla trampling and crushing buildings with his

enormous footfalls. This was devastation, Bruce Willis’s panic city – no twins

– a gaping hole left in the sky. Sirens, alarms, the noise was deafening.

People were screaming, crying. They hollered, turning me like a globe to run. I

couldn’t move. I could only think of Aunt Vagna and her flower shop near the

Trade Centre. The building now full of flames, falling glass, storey after

storey crashing into the streets of New

York.

New

York was falling apart.

* * *The Tin Hat Roof

Thump.

Thump. I hear the base of their stereo again today. I expected silence, and not

industrial production in the country. Even the wind is cutting into the shrubs

forcing their spring growth to continually brush the walls in an annoying way.

I had enough money to travel to France, but

then that would be dipping into my rainy-day savings, so I drove to Collie

instead, staying at a friend’s place.

It’s nice here, high ceilings, two walls of

electric heaters. It’s the old girl-guide hall renovated with a mezzanine

floor, curving wooden staircase to four bedrooms, a study-type office and a

kitchen on the lower floor. The only downfall is the bathroom and toilet

outside. So, yes spiders!

I had planned this seven day holiday in a hurry

and considered daily walks to the Collie

River. After a long and

wet winter with little exercise my clothes did not fit well.

I work for a company supplying animals to

the zoo, mainly studying marsupials, the endangered list and those species coming

on the list as threatened. So it was a refreshing change to stop thinking about

bilbies, bandicoots, yellow-tail wallabies, and probing dead placentas. I had

also planned a canoeing trip. The area has great facilities for slipping your

kayak or 2-man canoe into the river. A healthy river. I’ve walked its banks,

studied reptiles crossing my path. You catch the odd gecko loving the warmth of

your hand.

Thump. Thump. The neighbours are into rap

and fucking new forms of musical excitement.

The walls are shaking and their music is

penetrating the landscape. Without the mezzanine floor, the hall is one large

chamber. You remember those country balls and dances? It’s much the same,

asbestos, tin roof, four oblong windows down each side, double front doors and

a rear stage. The stage has been orchestrated into a lounge room with wooden

rails and a slow combustion stove. Very cosy.

Now the walls are slanting, shaking back and

forth as if this house is gyrating to next door’s music. It’s sort of doing a

slowed-down shimmy.

Unlocking the padlock, I open one of the

side doors. The house next door on the right has fallen to the ground. I look

over the fence to the main road, and women are dashing from their

partly-collapsed houses. The man next door, who I don’t know very well, bounds

out to the street, yelling, ‘Call the fuckin’ brigade.’

In earnest, I yell across to three

teenagers, one clutching a pet.

The ground is moving under my sneakers, so I

decide not to venture any further. Out the front, the shattered remains of the

owner’s landscaped gardens; the two grey gums have fallen to the ground with

trunks snapped like a match. The angle and heaped branches are ominous like the

beginnings of a cairn or pyre.

The previous spells in the tremors occur less

and less now, so I quickly trundle my gear back and forth to the car. Lucky for

me, the car was parked up on the road and not down in the gully-flat where the

hall is. By now, the place has moved from its stumps. It’s about to slide

sideways. Then another violent surge shakes the iron beds and rattles the

windows. The hall wobbles on its foundations, shaking like a dog full of sea water.

The walls become human, inhaling, exhaling until it huddles into itself,

concertinaing down like one of those

buildings under a wrecking explosion of gelignite.

Driving along

the highway, with tears finding an exodus from my eyes, I feel like an

accomplice to the hall’s demise.

On the six o’clock news, the earth tremor

recorded 4.8 on the Richter scale, the highest one ever in the southwest for 40

years. But that was Katanning! Then a cut to an ING commercial makes me wonder

about Larry’s insurance policy. Does he have one on the hall, or not?

Tomorrow I’ll ring him. No! email him in America and

unfold the terrible news about the earthquake, the hall’s lost history, and how

it disappeared into the earth with only the tin roof exposed like a hat on the

land. Well, what else can I say?

* * *

Moving Through Myth

The horses are

green and scarred. We are gazing at Percy Wright's carousel seventy-odd years

from its turning. Voices travel on radio waves, and we hear the volley of

summer, think of women mingling at the water's edge, a lifeguard above our

heads in a little yellow cap.

Somewhere in the heart of the room we

enter an old era. Leanne moves through the corridor dressed in a floral dress,

wearing cork sandals; her red polished toenails entering daylight. I look

equally like her couture, except I’m wearing autumn prints in rayon to mid-calf

with a Peter Pan collar.

We do not miss our part of town as we walk

along the jetty, climbing grass dunes scattered with firs. Carnival shouts,

sounds of tent pegs, a horizon of mirrors! Horses with clumps of flaxen hair

rock back and forth, braced on metal hangers.

Leanne says, 'This is a great aperture for making art.'

'In Paris,' I say, ‘Eugène Atget photographed a dying era as

artifact; an organ grinder, satyrs, a brass carousel with bulls and decorative

cups.'

We move on through myth, into the canvas of street fairs and

sideshows; the freaks of carnival. This is their home, their location. They do

not move, and only when the organ begins do they smile gently as we pass.

In the background, the operator lights a cigarette, and his smoke

merges into a distant factory’s plume that disappears into tiny clouds above

us. Young women are languid on the carousel in beach kimonos & skirts,

clutching horses. Some link arms as if on a Sunday stroll. Leanne and I watch

them laughing, placed there together, as if they are the rare smiles of our

mothers and grandmothers arranged in sepia.

Out in the air trombones pulse; the wind begins a slow refrain

through the scaffold of horses. The silky women slip like soap from saddles,

rhythmically lifting and lowering their buttocks around the gallopers. We laugh

at their antics.

Leanne says, ‘Soon they will raise their skirts above their knees

and kick out a Charleston.’

South Beach 1932; the day shifting like a seagull on Percy

Wright’s Carousel, a foreshore of miniature cars, hot dogs, Hoop-la, and

porcelain clowns. An aroma of hot tea and smells of sawdust trail through the

courtyard, and the women are still smiling. Their faces float past, and the

music begins again.

I do want to be beside the seaside. Oh, I do

want to be beside the sea.

The trees swoosh by, the grass beneath our feet, as our hands

trace images across the way: an ice-cream van, a shooting gallery, lucky wheel,

a man arranging carnival toys. We sway, our heads cocked back, looking up at

the sky, clanging our garish horses until the paint peels. The trumpets and

cymbals falling soft as a mist on a bald mountain; carnival's razzle-dazzle

winding down its pulse, vivid stripes of fringed stalls and tents abandoned in

the failing light.

Raising the tent-flap, we watch the women swing arms over a

distant hill, and as the clouds couple at dusk, our path downhill leads us

through shadows, our bodies silhouetted before us.

I say to Leanne, 'What did you enjoy the most?'

'Letting go of the red and green balloon,' she says, 'and how the

rippled shoreline left holes at our feet.'

* * *

Life is Not a Box of Lamingtons

Sarah rolled over, moaned and hugged her pillow. She

wanted to slip back into the shadows, back into the memory and desire. He was

the object of her pursuit. She had taken him there in the shadows. In the dark

she had lost all inhibition, pressing herself against him on the brick wall of

the dark alley. She was where she wanted to be, at the base of his body guiding

him to her. In the short moments of her desire the mind had played tricks on

her, suddenly it teased him forward, then turned him around, then finally,

faded him out like mist.

The door opened and the morning light streamed across her

bed. Then a heavy, solid shape opened the window and the breeze rattled the

verticals.

We're out of

coffee!

What time is it?

Ten past six.

Sarah pulled the

blankets over her head. This was all too much. She wanted privacy. Aaaargh! she

groaned. She wanted to slip back into the dream - into the memory of his sex.

She had seen him somewhere before; gold earring, ponytail, but this guy didn't

have red hair.

I can't wait with

breakfast all day, called her mother.

Sarah let the hot

water of the shower soak into her skin. She wrote the word resign into the

misted glass. Combing her long wet hair, she emptied a large suitcase on her

bed. The idea of her own place made her smile. She was cooking a meal for two,

feeding birds and her own dog. She was opening a large door to a backdrop of

ghost gums. Walking in the bush gathering banksia cones. Now the two of them

were running, jumping logs and stopping to hold hands. This was all she could

think of, holding a young male body close to hers, smelling the freshness of

his long hair, touching the traces of her dream.

She counted the

notes and coins in her purse and looked at a faded bank slip. Suddenly she felt

a sense of guilt. With father gone, she would be another one to hurt, twist the

knife. It was only a saying that 'a mother could look after five children, but

the five children couldn't look after one mother.' She had been loyal. She had

tried to please, tried to ease a mother's pain, but father's leaving hadn't

equipped her for those horrible loud, incessant wails at night.

Mother. She was

the problem. She couldn't talk to her any more about anything, not even the

nightmares of the job. Her life was filled with police jargon, she lived it,

breathed it. Her short sharp answers were like metal shavings falling from the

rigours of her day. Days that were filled with frustration. It was her way of

letting go, but this was a language mother could not tolerate. So, when the

friction eased after the slamming and rattling of teatime dishes they found

solace together in criticizing TV soapies or lambasting the cruel pranks on

'the funniest home video show.'

Sarah gazed out of the window into the

incredible day. She couldn't understand how the northern suburbs, once sparse

and quiet, had suddenly become inundated with criminal and traffic offenses.

Even as far north as Gingin some streets harboured lives of misery. She had

hoped that it hadn't reached Jurien Bay, the holiday haven of her childhood.

But the long hours were getting to her and this was not how she wanted to live.

Choices. She had choices to make. She scanned the

newspaper columns. Turning to the situations vacant, she frowned on words like

sales trainees, accounts payable and telemarketers. Carella stood beside her

and quietly reached in and folded her newspaper.

Time to go -

another break in!

They walked past

a young child leaning on the boot of a car, silent, except for the sucking of

fingers. A smile came as Constable Sarah Maitland crouched and removed her blue

cap. Eye level with the child, she saw a little blonde girl in a photograph

sitting on her father's lap.

Where's mummy? asked

Sarah.

A wet finger

poked the air.

You're not lost

are you?

The child gurgled

and jiggled, then ran towards a woman in a blue-spotted dress. The woman

quickly pulled the child to her hip. Whingeing about the queues at the

check-out and the so and so's, she avoided the reproachful eyes of Carella.

Take the child in

with you next time, cautioned Carella.

Back in the

panel-van, Sarah clipped her belt and tucked the newspaper under her seat.

Looking for a

flat?

No! - I can't believe that woman!

Sure, you were. I

saw you.

The two-way

crackled.

We're on our way

Serge, over!

Sarah watched the

mother strapping the child into a safety seat.

I'll ring Lance,

the youngest brother. He's the new caretaker in one of those new Joondalup

studio apartments. They're not bad and they're only one hundred and twenty a

week.

I might not want

to live in Joondalup, said Sarah, watching the woman indicate as she was

watching her.

Sure you do,

close to work.

The two-way

clicked in.

Yes, Serge, yes,

yes! It's just thick, over!

Find Seacrest for

me please. The woman's pretty upset. He's got a thing about thick hair, you

know? All us Carellas have thick hair. Thicka Italian hair eh?

They arrived at a house at the end of the street. Leaving

the car, Maitland screwed her face at Carella.

I'm not

introverted. I like the quiet, maybe Two Rocks or Yanchep.

I'd have to drive

you all that way.

Carella pressed a

lifeless doorbell. An English voice greeted them from behind a security screen.

Come in duckies.

I was out shopping. I thought something seemed odd, you know queer like and

then I saw it, in the hallway, well!

What did you see,

Madam?

My son's CD's and

our hi-fi stuck in their bag. Well, when I walked into the kitchen there they

were. Right little devils, eating my lamingtons!

Lamingtons? asked Sarah, raising her eyelids.

Yes, I made them

for the school tuck shop. Here have one.

Carella put both

hands in the air. Sarah held the lamington over a plate.

Lamingtons. They were a sign of her school days. Bought

at the school fete or they sat near the coconut ice on tables in the Girl Guide

hall. She had taken them with a friend to her grandmother's house, where the

sticky bits floated in sauces of weak tea, while they giggled at Oma's raucous

laugh. Mrs. Meyer was a treasure, but more a treasured memory of German

culture, embroidered linen, Mozart and Brahms. Sarah remembered her long

hallway of fine china and wall hangings and rooms full of musty, old books.

Most of all she remembered the sweet cadence of her words like liebchen, schuss

and schnugglemouse.

Carella coughed

loudly. You all right Constable?

Yes, I'm fine,

fine. If we could have your name please, for the record - Mrs?

Wade, Angela.

Mrs. Wade related

the incident with the two intruders. They had cut the flywire in the kitchen

window and left black sand in the sink and on her floor. One had rushed past

her, and out the door. The other boy had also tried. She ran after him she said,

yelling to come back and clean up the mess. She managed to grab him and

struggled with him on the front lawn. Then she tied him up with some old rope

from the back shed.

You mean he's

still here?

Both officers

walked down the path. In a corner of the yard, tied with thick rope was a boy,

red faced and struggling to get free.

What's your name

son? queried Carella

You've got bad

breath, spat the boy.

Watch it. You

know you're in big trouble. Where do you live?

Around.

Ha! A know-all at

ten.

Carella unwound

the boy and bundled him into the car. 'Yes Serge, we're bringing the little

spitfire in now, over!'

Sarah remained

quiet. She wasn't pleased with herself. She had told Carella about leaving home

and hadn't wanted to, not yet anyway. Now he was organising everything, taking

her to some apartments after their shift. The lamington stuck somewhere. She

couldn't look at the boy. How many had she seen like this? She lost count. She

was somewhere else, packing and unpacking; handing money over to a man with

thick dark hair, turning on her telly, cooking dinner in her microwave. Opening

a door to the young man with long hair.

Sergeant Magee swivelled his chair behind a large desk,

his face furrowed, his fists were tight. Sarah hoped she would never have his

hard heart. She wandered away from inquest and the finger printing process.

Suddenly the boy

made a dash for the automatic door, and they were after him, bolting through

and out the building. Sarah had lapsed into a daydream and any concentration of

holding the boy and keeping him in her gaze had vanished into forests of old

ghost-gums, hollyhocks and timbered cottages.

Unforgivable!

yelled Magee. We've got him, but no

thanks to you. Get your mind back into gear Maitland. It should be here in

Wanneroo not on holiday somewhere!

One of the

officers interrupted.

I've had that

lady on the blower Serge at thirteen Seacrest. Says she's changed her mind

about pressing charges. Said something about doing her Christian duty, charity,

forgiveness and all that.

Sarah relaxed her

shoulders. It was over. She couldn't look anyone in the face. She felt

humiliated. Tired. Downtrodden. She handed in her report sheet and left through

the front door. Carella came after her. Told her to relax. Not to worry. It was

just a job. No big deal. Magee will be calmer in the morning. Carella held her

chin and wiped a tear from under her eye.

Come on, we're

going to those apartments I told you about.

They walked down the brick paving of the newly landscaped

apartments. The two-storey building of cream brick in a paintwork of blues and

creams and French lattice sparkled under a cloudless sky. A young man washing

his car waved. Sarah's jaw dropped and a hot surge rushed and flushed her skin.

Carella introduced Lance. Lance with the big smile. Lance with the thick dark

hair and ponytail. Lance with the earring. Sarah froze and blushed from cheek

to cheek.

Sarah, Lance.

Lance, Sarah. grinned Carella.

She climbed the steps. Turned the key slowly in the front

door. Walked into the lounge room. Turned on the light. She could hear the

heavy breathing coming from the family room couch. She read a note under a

fridge magnet. They were out of milk. LASAGNA IN THE OVEN. Reaching down into

her bag she pulled out a piece of paper. Picked up the cordless handset of the

telephone and walked into her bedroom. Lance's number stared up at her like

rows and rows of street numbers that led to dark alleyways. She dialed the

first three, then clicked it down. She balled the piece of paper round and

round in the palm of her hand.

No! She thought.

I can't leave her. Not now. I haven't got the heart.

0 comments:

Post a Comment