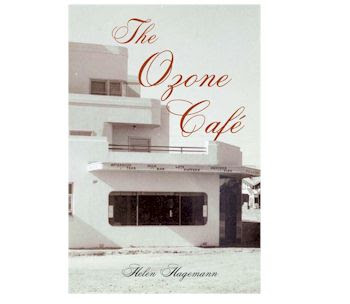

Artwork:

Arts Centre Cafe by Daniela Selir (1994)

Entering this competition as part of my writing practice. My story is a bit bleak, however the artist Daniela Selir would have known about the Fremantle Arts Centre as a historic women's lunatic asylum (1865-1901). A blue figure on the top right hand dormer window is not there by chance. And so I have capitalized on this, the knowledge of the cafe, its history and because I teach there each Friday fortnight. The cafe being the writers' favourite place at midday.

I

wanted the day to go faster, the morning to take its course. I walked by the

comfort of the ocean, over the bridge, past the cubed design. I reached my

favourite place, the Arts Centre Café, had a glass of mulled wine. It was soothing

and delicious. I never made it at home. I couldn’t put a finger on it, but

there was something peaceful about the complex: vintage rooms, very gothic,

artists mingling, the general public enjoying exhibitions, as well as the coffee.

I told the receptionist about the cardigan

I’d left behind, and that I’d return the keys so she wouldn’t worry. I knew

where the window was. Found the dark room, eased open the latch, lifted

the frame slowly and climbed out onto the roof. Not much point rushing things.

Midday under the blue canvas umbrellas, and the courtyard was packed mostly

with women, laughing, chatting over tea cups. Probably been to an art class;

pastels, water colours or ceramics, something like that. I wanted to do oils

once, before the baby.

I was too young to have a baby. Alex, my

boyfriend, was passive and wouldn’t help, or discuss my desire to terminate the

pregnancy. When I went full term, my parents doted endlessly, pleased about having a grandson, the little fellow’s fuzz of black hair, running in the family. Said his little ears sat like pressed

cauliflowers alongside his head. Father laughed at the bright twinkle in his opal

eyes. Like stained-glass windows or more like a bright morning vista, rising

over the hillsides.

At six months, I couldn’t believe he was real.

The birth certificate stated he was real. And all the baby photographs that

lined the window coffee table showed little grasping fingers touching

everything; a padded bottom sagging in blue leggings, spring bouncer hanging

from the doorway.

An

empty space left. I put the bouncer in

the recycle bin. It had lifted the paint, leaving two holes in the lintel.

The handyman never turned up.

I couldn’t bear to look at the

photographs any longer, so I shoved them in the bottom drawer.

Alex didn’t feel sorry for me. He blamed

me. ‘I told you, over and over, get some help.’ That’s all he could ever say,

when he was around. Three nights a week he went out, down the pub, to a card

game or to footy training. He never even changed a nappy. He didn’t like the

crying. I didn’t get any sleep, either. So I don’t miss his nagging. Blah,

blah, blah! ‘This is wrong, that’s wrong, what’s to eat?’

He wasn’t going to marry me anyway. Good

riddance to bad rubbish.

I had a suitcase packed for a long time.

Just wanted out, too many questions. Why this, why didn’t you do that? The baby

looked so still. I couldn’t see the colour of his eyes anymore. All babies’

eyes are blue, aren’t they?

Father said I needed to rest. I wondered

about the severe conversations with the doc outside the door. I think they said

I wasn’t to mix the vodka with the pills.

Ha!

I know I had the baby, but I didn’t

recognise him as a baby. He was Conrad. Conrad wouldn’t stop crying. I screamed

at him. I screamed at this creature, this vile creature. Screamed and screamed

at the blood on the wall.

Oh! the headaches, my temples pounded. My

parents only nodded and cajoled, but they didn’t understand. They couldn’t

help, and they wouldn’t answer their phone, but that was when mother got sick. At

the time, I grew afraid of the dark. I know that sounds stupid, coming from a

grown up, but the dark side scared me.

I

cried like a baby when mother died. One year after Conrad. Father stayed barefoot and remained in his

dressing gown all day. I waited for his

voice to return. Sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t. He got all choked

up.

Last night I went to the river. The

waterfront was not considered a safe place because of other drowning victims.

Hundreds each year took the long plunge off the bridge, and hundreds more

simply waded into the water. I thought it would be easier there as despair

collects in the night’s veil of humidity. I thought I heard someone scrabbling

up the bank, and there was a trace of a foul, brown odour. I guessed mud or

detritus. But it was as if the river had regurgitated one of its dead. Late

into the night, it wasn’t uncommon to see writhing shapes caught in the tidal stream,

or the black symmetry of heads bobbing in the little hollows of waves. I had to

tell myself they were just shadows made by the pattern of the moon’s glow.

I had to get out of there. I walked

towards the Town Hall. It was late, but I managed to grab a newspaper left in

front of a newsagent stand. There was nowhere to leave any money, so I figured

I owed them.

The river was a horrifying place, that’s

why when I woke this morning, the idea of sneaking through that window at the

Arts Centre occurred to me; a curtainless window high enough on the second

floor so that I could look out over the lawns, treetops and gardens. An old

historic building, peaceful in its repose. I knew I could climb higher if I had

to, secure myself behind a chimney stack before finding the right ledge, the

right footing. The secret is, you never look down, only up or sideways.

I had been there an hour when I heard a

loud siren. It scarred the life out of me, but I managed to hang on. Some sort

of fire drill, I assumed. I could hear voices closer to the windowed room, then

a series of muffles and thudding shoes descending the stairs.

One o’clock and classes seem finished.

Not the diners in the café, though. I wanted all the women to go home, I wished

really hard that they would all go home.

What? What a commotion! Hey! What the…? One of the women, who I spotted earlier

under an umbrella, butted out her cigarette, her puff of smoke aimed towards me.

The café waiters, three in all, had gathered in the courtyard, their necks

craned upward. Someone pointed at me, calling out a nasty profanity. Another

café patron arched his hands like window shades over his eyes, his face askew.

The air burst an arrangement of shouts, ambulance

and other sirens. Not again, I thought. It happened last year, and the year

before. They’ll show my diaphanous dress on the seven o’clock news. They always

spoil things for us.

I

heard the constant, crazed megaphone pleas. Now a man in uniform raised the

window higher, held his hand out towards me. I couldn’t believe that such a

large body could squeeze through that tiny space. So this time, I decided to

move around to the east wing. Down below, there was a man in a white coat, other

uniforms, someone calling. I spotted six or seven firemen guiding a white

trampoline into position, and this policeman barely able to walk over the slated

roof, reached out again, begging me in a silly voice, the five fingers on his

right hand splayed out, wavering them back and forth like he was trying to grab

my fragile, svelte body.

I didn’t want another man, touching me,

ever again, so I jumped.

Copyright (c) 2017